See below for the English version

Le sere d’estate, al tramonto, le donne sedevano sulle sedie basse di legno e paglia nella piazzetta di ‘chianche’ bianche. Mille rondini disegnavano cerchi concentrici, i loro gridi tagliavano il cielo rosa, il campanile del vicino convento segnava le ore. Le donne battevano con pietre lisce, di forma ovoidale, su lastre di pietra, per togliere la buccia alle fave secche. Alcune lavoravano all’uncinetto, altre farcivano con una mandorla i fichi tagliati in due, che avrebbero messo l’indomani a seccare sui graticci al sole.

Le donne recitavano il rosario, e poi parlavano, parlavano sottovoce, un brusio continuo sino al momento di andare a dormire. Raccontavano di chi non c’era più, di chi era andato via da tempo e non era più tornato; raccontavano di quando erano ragazze dalla pelle tenera, della raccolta delle olive, di sguardi innamorati durante la vendemmia. Ricordavano feste di nozze, un viaggio di giorni sul carro per raggiungere il mare; ripensavano al pellegrinaggio sotto le stelle d’agosto verso il santuario di campagna. Rievocavano la guerra, la fame, il pane con la segatura, la paura, i rifugi nelle grotte vicine durante i bombardamenti. Poi, abbassando ancora più la voce, parlavano di tradimenti, di amori illeciti, di incesti.

A noi bambini piaceva ascoltare, anche se non capivamo tutto; ci immaginavamo volti giovani, braccia forti, occhi desiderosi, sentivamo incantati quei brandelli di racconti come fossero favole. Il passato, grazie alle parole, perdeva ogni oscurità e ogni dolore. Nel nostro piccolo cuore metteva radici la speranza di un futuro migliore, dove il peggio ormai era alle spalle e malattia, morte, dolore non avrebbero gettato più ombre. Non sapevamo che il passato non è mai davvero passato.

Le donne raccontavano e battevano sulle lastre, sbucciando le fave. Qualcuna invece guardava fisso il cielo, gli occhi sbarrati, inseguendo pensieri, prigioniera di ricordi o di malattie, prigioni della mente, malattie di cui allora non si conosceva nemmeno il nome. Col passare del tempo le donne a poco a poco sparivano, le sedie restavano vuote, i volti segnati dal sole e dal tempo finivano nelle immobili fotografie bianco e nero stampate sui manifesti da morto. Ancora oggi, nei paesi del Sud, i morti danno l’addio al mondo affacciandosi da fotografie ritoccate sui manifesti, come da finestre.

Cosa resta di quella piazzetta affollata al tramonto? Sulle pietre bianche e antiche hanno versato cemento e asfalto; lo slargo c’è ancora, soffocato dai musi delle auto parcheggiate. Il campanile non segna più le ore, suona solo per i funerali o la messa di domenica; il convento delle suore è vuoto, le finestre murate. Le rondini paiono stremate dalla sete e dal caldo.

Dove sono le donne sedute a parlare tra loro fitto fitto? Forse in qualche cassetto riposano le loro fotografie stampate per il funerale, i cosiddetti ‘ricordini’ da dare agli amici o ai parenti, piccole foto con una croce o una Madonna, che portano sul retro una frase del vangelo o qualche parola di lode. Al cimitero del paese, sotto alti cipressi, stanno le loro tombe, alcune adorne di fiori, altre abbandonate.

Cosa resta del passato? Cosa resta di noi? Ecco la domanda alla base del testo poetico e struggente dello scrittore e sceneggiatore Kiriakos Haritos, Thebae Desertae, un dramma scritto appositamente per il Festival di Epidauro e per la prima volta in scena il 4 e 5 luglio nel ‘piccolo’ teatro greco di Archaia Epidauros. Difficile immaginare uno spazio più adatto per questo testo che trabocca nostalgia e rimpianto.

Epidauro antica è un villaggio che si affaccia sul Golfo di Saronico, con un piccolo porto dal mare blu intenso, un promontorio che divide in due la costa, a una decina di chilometri dal teatro grande e dai resti del santuario di Asclepio. Il teatro ‘piccolo’ non ha l’imponenza inquietante di quello ‘grande’ e celeberrimo; non si precipita ripido verso l’orchestra, dando vertigini. Eppure la vista del sole che si spegne in un manto dorato sulle alture dell’Argolide e sugli avvallamenti profondi e bui, l’affacciarsi prepotente della luna e delle stelle in un cielo di piombo, rendono questo luogo sacro, dolce e misterioso insieme. Dai gradoni di pietra carezzati dalla brezza si ode il rumore delle onde e si intravede uno stralcio di mare. Poi, dopo che l’ultima luce del sole si è spenta, risuonano gli echi nella notte, il frinire incessante delle cicale, il fruscio delle foglie di aranci, l’abbaiare di un cane.

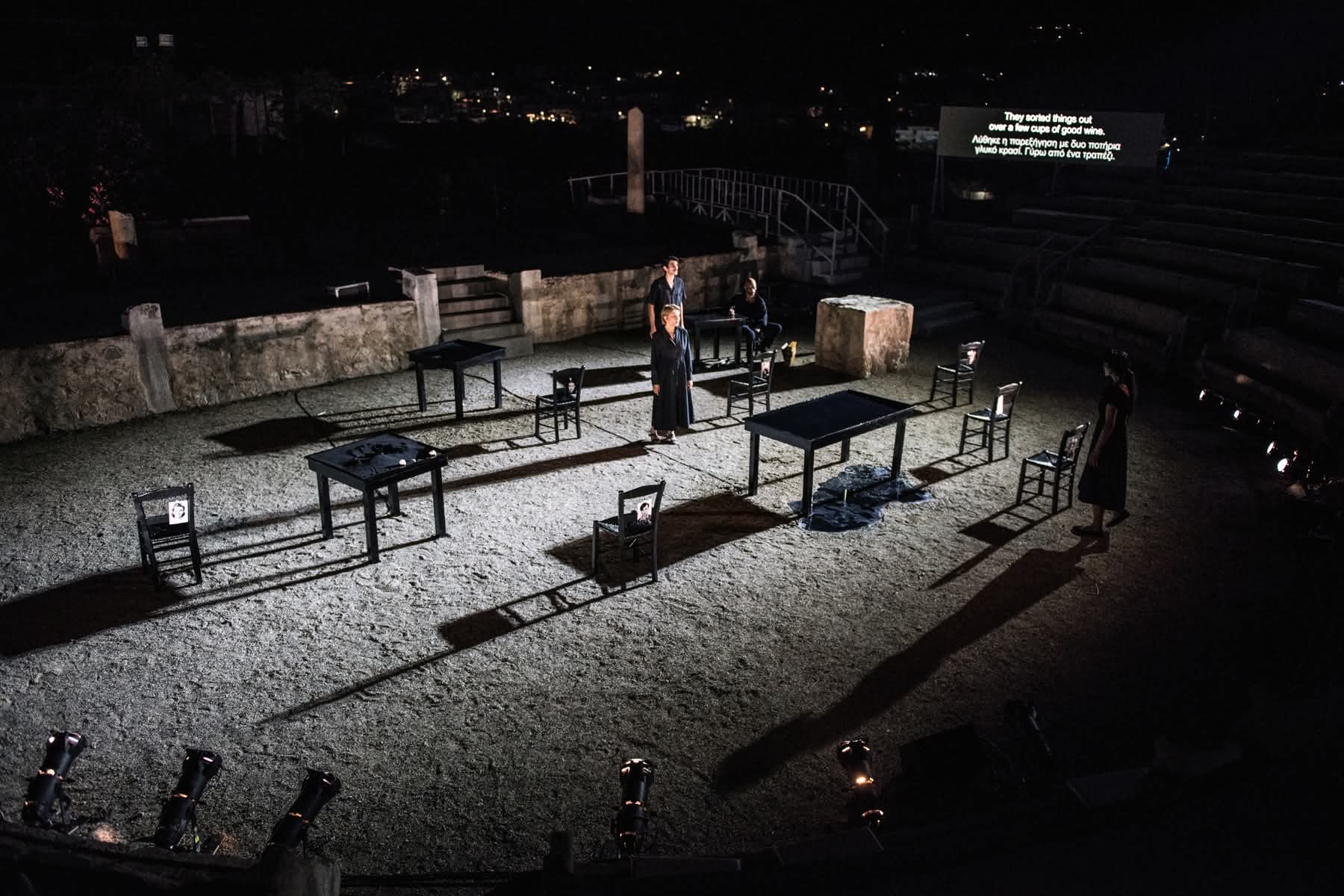

Nell’ orchestra del teatro sono disposti i tavoli di un’osteria abbandonata, neri e sgombri; il luogo è deserto, ma vi si aggirano ombre, fantasmi, si intendono voci di un passato forse remoto, forse recente. La skené antica è sostituita da una casa in pietra, una casa contadina, costruita forse nel XIX secolo. Il passato si intreccia al passato, le ombre incontrano altre ombre. Gli attori, vestiti di nero, entrano in scena proprio dal cortile della casa, come se si trattasse della gente che un tempo la abitava.

Siamo a Tebe, ossia in un luogo nel Mediterraneo tra gli aranci e i limoni, un luogo sepolto dalla polvere della storia. Tebe: metafora di ogni manciata di case battuta dal sole e dal vento nel Sud del mondo. Mi sembra, per un momento, di essere tornata al mio paese della Puglia, alla piazzetta dove al tramonto le donne sedevano e raccontavano.

E anche qui, tra questi tavoli dove da tempo non siede più nessuno, una donna comincia a raccontare una storia nota: due fratelli che si uccisero per impossessarsi della terra ereditata dal padre, ma che non volevano dividere tra loro; una sorella dal nome «ancestrale», Antigone, nata per amare e per onorare i morti; raccontano di una madre straziata, di un uomo che commise incesto senza saperlo. Raccontano del padrone di turno, che precipitò nella sventura per arroganza e perse tutto, compresa la sua famiglia. I racconti sono noti, ma li ascoltiamo ancora e ancora, spezzati in frammenti, pezzi di una tela tessuta, scucita e ritessuta ancora. Le parole diventano immagini, come negativi sviluppati in una camera oscura, fotografie che sbiadiranno: l’acqua della pioggia e del tempo laverà ogni cosa abbandonata, scorrerà in rivoli per le strade, si depositerà nelle pozzanghere.

Sarà vero quello che si racconta? Oppure è un’invenzione, per passare le serate d’estate, prima che venga notte fonda? Ogni racconto è racconto di morti, ogni racconto è traccia del passato impressa nella polvere, traccia che una folata di vento improvvisa porta via. E quei nomi famosi – Eteocle, Polinice, Antigone, Ismene, Edipo, Giocasta, Emone – sono nomi di uomini come noi, che come noi hanno dovuto confrontarsi con il mistero della morte, trascinati dai sentimenti e dalle ambizioni, che si sono abbandonati alla violenza e alla dolcezza dell’amore. Le storie di quegli uomini e di quelle donne, come in una danza, si intrecciano e si sciolgono, vengono ripetute, poi dimenticate, poi riaffiorano alla memoria insieme a un profumo, a un rumore, a una canzone. Ognuno di noi ha la sua Tebe abbandonata, ognuno di noi ha i suoi volti impressi nella mente, ognuno di noi ha conosciuto dolori e gioie, lutti e traumi: ognuno di noi sta solo sul cuor della terra, ed è subito sera.

E cosa resta? Un brusio, un racconto, una consapevolezza: ἀνθρωπάκος ἤμουνα, I was but a man, non ero che un essere umano, pronto a schivare i dolori della vita.

Questi ‘frammenti’ di Kyriakos Charitos, portati in scena da un ensemble perfetto, magistralmente diretto da Olia Lazaridou, sono preghiere, lamenti, racconti, canti sul filo della musica composta da Jan Van Angelopoulos che non è un accompagnamento della performance, ne è l’anima. Le parole scandiscono il ritmo, si associano al battito del cuore, si seguono col fiato sempre più corto: siamo sospesi nella magia della notte e del tempo. Talora sembra che le figure in scena scompaiano, e le voci diventano sussurri nell’oscurità, lacrime cadute dalla luna sospesa sulla valle o gocce della schiuma della risacca. Farfalle notturne e cieche.

Cosa resta del passato? Cosa resta di noi? Ombre che ci vengono a visitare, sogni che ci svegliano d’improvviso, ricordi che ci confondono, lacrime negli occhi senza apparente motivo, luoghi che non esistono più, abbandonati. Restiamo noi e i nostri ricordi - ognuno sta solo sul cuor della terra - resta la nostra inevitabile solitudine, perché infine tutti devono andar via, non si sa verso dove, tutti ci lasceranno oppure saremo noi a lasciarli per primi. Resta il nome di chi abbiamo amato, odiato, conosciuto; restano fotografie sempre più sbiadite.

Resta una piazzetta dove sedevano le donne al tramonto, battevano su lastre di pietra, ridevano tra loro, oppure guardavano pensose verso le rondini impazzite in cerca di un ricordo, le rughe sempre più profonde, e raccontavano di quando, in guerra, una ragazza trovò il fratello per strada che era stato impiccato dai fascisti e lasciato a marcire e lo tirò giù, lo lavò, lo seppellì nonostante il divieto, e allora…

The Past Is a Foreign Land: Thebae Desertae at Epidaurus

Summer evenings, at sunset,

the women would sit on their low wooden and straw chairs in the little square paved with white chianche.

A thousand swallows traced concentric circles in the sky, their cries slicing through the rose-tinged dusk,

while the bell tower of the nearby convent marked the passing of time.

They struck smooth, ovoid stones against slabs of rock to peel the skin from dried fava beans.

Some crocheted in silence; others pressed almonds into halved figs,

preparing them to dry the next day on reed racks in the sun.

They recited the rosary, then whispered in low tones,

a constant murmur that lasted until the hour of sleep.

They spoke of the ones who were no longer there, of those who had left long ago and never returned.

They recalled their girlhoods, soft-skinned and sunlit, the olive harvest,

the glances exchanged in vineyards heavy with grapes.

They remembered wedding feasts, days-long journeys by cart to reach the sea,

and the August pilgrimages under the stars to the country shrine.

They evoked war, hunger, bread made with sawdust, fear,

and the hiding places in nearby caves during the bombings.

Then, lowering their voices even more, they spoke of betrayal, of illicit love, of incest.

We children loved to listen, though we could not grasp everything;

we imagined youthful faces, strong arms, eyes burning with longing.

We listened, enchanted, to those fragments of stories as if they were fairy tales.

Through words, the past lost its shadows and its pain.

And in our small hearts, the hope of a better future took root—

a future where the worst was already behind us,

where sickness, death, and sorrow would no longer cast their dark veils.

We did not yet know that the past is never truly past.

The women kept telling their stories and striking the stones, peeling the beans.

One of them, instead, would fix her gaze on the sky, her eyes wide and still—

chasing thoughts, imprisoned by memories or by illnesses of the mind,

sicknesses for which, then, there were not even names.

As time passed, the women gradually vanished;

the chairs remained empty,

their sun-worn faces ended up in unmoving black-and-white photographs

printed on death notices.

Even today, in the villages of the South,

the dead bid farewell to the world by leaning out from retouched portraits on funeral posters—

like figures at the windows.

What remains of that small square, once crowded at dusk?

The ancient white stones have been smothered beneath cement and asphalt;

the open space is still there, but now suffocated by the snouts of parked cars.

The bell tower no longer marks the hours—

it tolls only for funerals or the Sunday mass.

The convent lies empty, its windows walled in.

And the swallows seem exhausted by thirst and heat.

Where are the women who once sat so closely, speaking in murmured tones?

Perhaps their photographs rest in some drawer,

the ones printed for their funerals—those so-called memorial cards

meant for friends and relatives:

small portraits marked with a cross or a Madonna,

bearing on the reverse a verse from the Gospel or words of gentle praise.

In the village cemetery, beneath tall cypress trees,

lie their graves—some adorned with flowers, others long neglected.

What remains of the past? What remains of us?

This is the question at the heart of the poignant and poetic work

by writer and screenwriter Kiriakos Haritos, Thebae Desertae—

a drama written especially for the Epidaurus Festival,

staged for the first time on July 4th and 5th

in the ‘small’ Greek theatre of Archaia Epidauros.

It is difficult to imagine a more fitting setting

for a work so steeped in nostalgia and longing.

Ancient Epidaurus is a village overlooking the Saronic Gulf,

with a small harbour of deep blue water,

a headland splitting the coast in two,

just a few kilometres from the great theatre and the ruins of Asclepius’ sanctuary.

The ‘small’ theatre lacks the grand, unsettling majesty of the renowned one nearby;

its seating does not plunge steeply toward the orchestra to induce vertigo.

And yet, the sight of the sun vanishing in a golden veil

over the heights of Argolis and the dark, deep valleys,

the bold rising of the moon and stars in a leaden sky—

all this renders the place sacred, tender and mysterious at once.

From the stone steps, caressed by the evening breeze,

one hears the sound of waves and glimpses a fragment of sea.

Then, when the last trace of sunlight fades,

the echoes of night emerge: the ceaseless chirr of cicadas,

the rustle of orange leaves, a dog barking in the dark.

In the theatre’s orchestra,

stand the bare black tables of a long-abandoned tavern.

The place is deserted,

yet shadows drift through it—ghosts,

voices from a past perhaps ancient, perhaps not so distant.

The ancient skéné is replaced by a stone house—

a peasant dwelling, likely built in the nineteenth century.

The past intertwines with the past;

shadows encounter other shadows.

The actors, dressed in black, enter the stage

from the courtyard of the house,

as though they were the very people who once lived there.

We are in Thebes—

or rather, in a place somewhere in the Mediterranean, among orange and lemon trees,

a place buried beneath the dust of history.

Thebes: a metaphor for every sun- and wind-scorched cluster of houses

in the global South.

For a moment, I feel I have returned to my own village in Puglia,

to the little square where, at dusk, women once sat and told stories.

And here too, among these tables where no one has sat for a long time,

a woman begins to speak,

to tell a story we all know:

of two brothers who killed one another

in a struggle to seize the land left by their father,

a land they refused to share;

of a sister with an "ancestral" name—Antigone—

born to love and to honour the dead;

they speak of a mother torn apart by grief,

of a man who committed incest unknowingly.

They tell of the ruler of the moment,

who fell into ruin through arrogance

and lost everything, even his own family.

These are stories we have heard before,

yet we listen still—again and again—

broken into fragments,

shards of a fabric once woven, unraveled,

and now rewoven anew.

Words turn into images,

like negatives developed in a darkroom,

photographs destined to fade.

The rain—and time—will wash away everything left behind;

it will flow in little streams through the streets

and settle into puddles.

But is it true, what is told?

Or is it invention, a tale spun to pass the summer evenings before the deep night falls?

Every story is a story of the dead,

every story is a trace of the past etched in dust—

a trace that a sudden gust of wind can sweep away.

And those famous names—Eteocles, Polynices, Antigone, Ismene, Oedipus, Jocasta, Haemon—

they are the names of men and women like us,

who, like us, were forced to face the mystery of death,

driven by emotions and by ambition,

who gave themselves over to violence

and to the sweetness of love.

The stories of those men and women

weave together and unravel like a dance;

they are told and retold, then forgotten,

only to return to memory with a scent, a sound, a song.

Each of us carries our own deserted Thebes.

Each of us bears the faces engraved in memory.

Each of us has known joy and sorrow, mourning and trauma—

each of us stands alone upon the heart of the earth,

and it is suddenly evening.

And what remains?

A murmur, a tale, a reckoning:

ἀνθρωπάκος ἤμουνα — I was but a man,

nothing more than a human being,

trying to dodge the wounds of life.

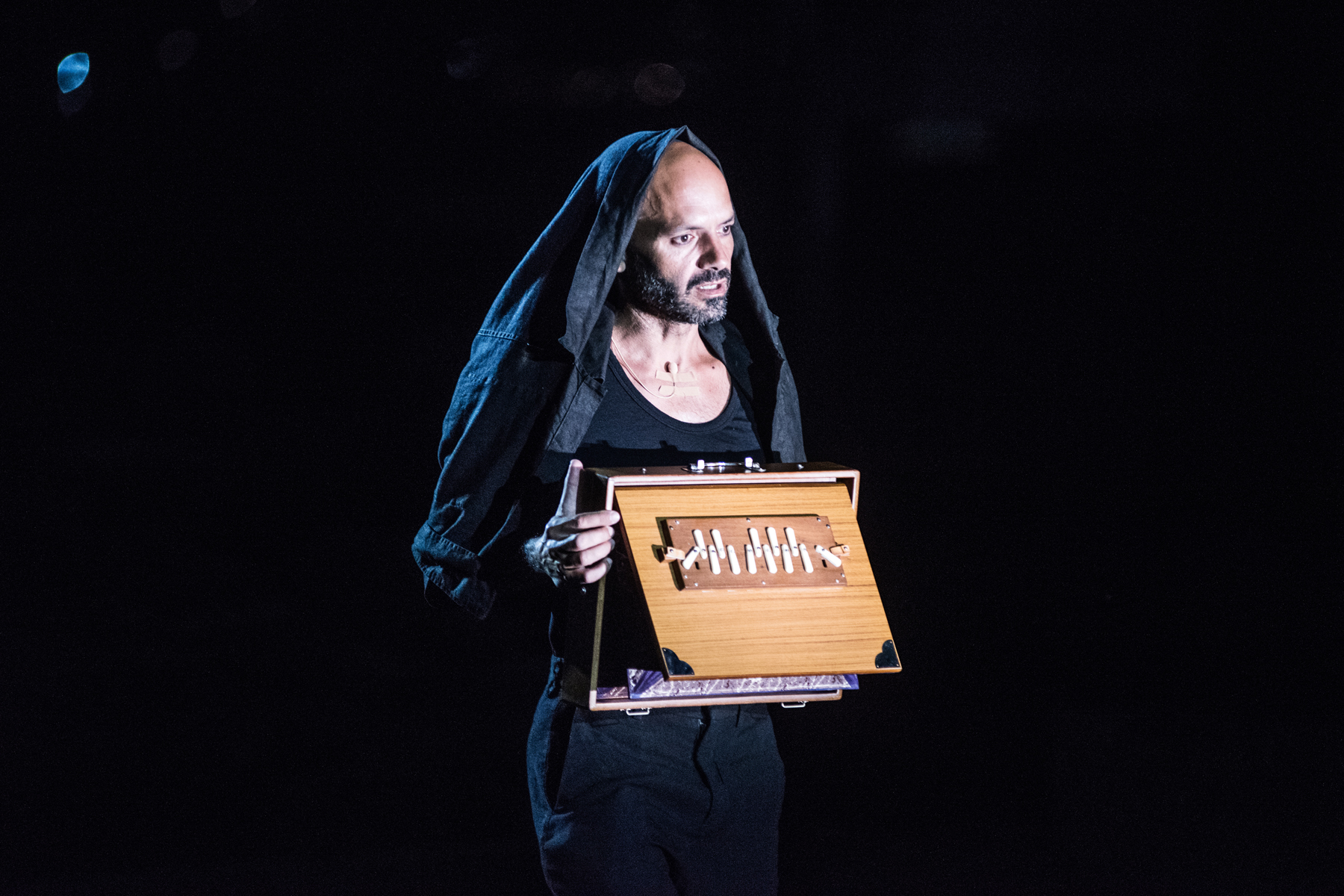

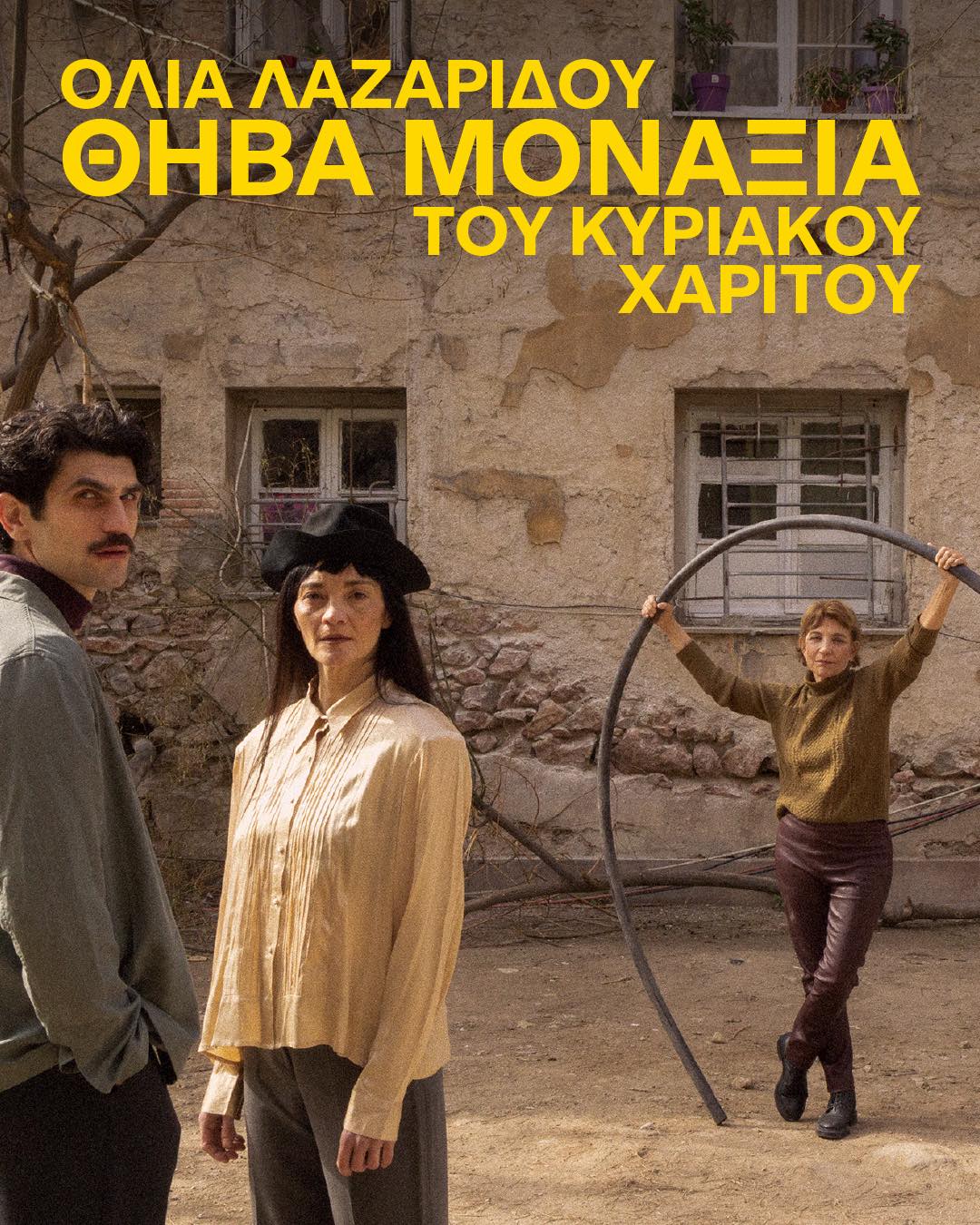

These fragments by Kyriakos Charitos,

brought to the stage by a flawless ensemble under the masterful direction of Olia Lazaridou,

are prayers, laments, stories, songs poised upon the thread of Jan Van Angelopoulos’s music—

which is not mere accompaniment to the performance,

but its very soul.

The words mark the rhythm,

they echo the beating of the heart,

they follow one another breathlessly:

we are suspended in the magic of night and of time.

At times, the figures on stage seem to vanish,

their voices dissolve into whispers in the darkness—

tears fallen from the moon hanging over the valley,

or droplets of foam from the breaking surf.

Nocturnal butterflies, blind and fleeting.

What remains of the past? What remains of us?

Shadows that come to visit,

dreams that wake us suddenly,

memories that confuse and disorient,

tears in our eyes for no reason,

places that no longer exist, abandoned.

What remains is us, and our memories—

each of us stands alone upon the heart of the earth—

what remains is our inescapable solitude,

for in the end, everyone must go,

no one knows where;

all will leave us, or we shall leave them first.

What remains is the name

of those we have loved, hated, known;

what remains are photographs, ever more faded.

What remains is a little square

where, at sunset, the women used to sit,

striking smooth stones on slabs of rock,

laughing together,

or gazing pensively toward the frenzied swallows

searching for a memory,

their wrinkles deepening,

telling stories—

of when, during the war,

a young girl found her brother hanging in the street,

lynched by the fascists and left to rot.

She pulled him down,

washed his body,

buried him,

despite the prohibition—

and then...

Direction Olia Lazaridou

Music composition Jan Van Angelopoulos

Set & costume design Angelos Mendis

Lighting design Eliza Alexandropoulou

Movement Nikoleta Xenariou

Vocal coaching Giannis Psalidakos

Assistant to the director Ariadni Konstantakopoulou

Sound engineering Nikos Kollias

Cast Alexandra Kazazou, Olia Lazaridou, Giannis Psallidakos, Vasilis Tryfoultsanis

Executive producer Apparat Athen / Nikolas Hanakoulas

Language Greek (with Greek and English surtitles)

Surtitle adaptation Michel Eleftheriou

The work is published in a bilingual edition as part of the Theatre Series of the Athens Epidaurus Festival, in collaboration with Nefeli Publishing. The English translation is by the author, Kiriakos Haritos.

Photo by @Karol Jarek