The English version below

Nell’orchestra del teatro grande di Epidauro, si erge l’ingresso di una casa borghese degli anni Trenta del Novecento, con una scala a chiocciola di ferro battuto, le persiane dipinte di verde, spalancate: il frammento di un edificio, una rovina architettonica. Manca tutto il resto della casa, la facciata, le mura: l’entrata porta nel vuoto del retroscena e nell’ignoto. La porta finestra sovradimensionata appare obliqua, scardinata, come una bocca pronta a risucchiare chi vi si avvicina.

La scena viene illuminata fiocamente da un lampione a olio. Non ci sono fiori né aiuole all’ingresso di quella che forse un tempo fu una villa con giardino, solo una panchina vuota in una corte spoglia e petrosa. Dalla porta d’ingresso viene fuori una nebbia sinistra, nubi di polvere, fumo di un incendio, ceneri del passato.

Il lampione si staglia sulla scena, inondandola di un’atmosfera nostalgica e romantica insieme. Viene in mente la ‘lanterna’ protagonista della canzone irradiata dalla Radio militare della Belgrado occupata dai tedeschi in piena guerra mondiale, il 14 agosto 1941, Lili Marleen, resa celebre dalla voce scura di Marlene Dietrich: quella canzone – com’è noto – diventò un inno di speranza pacifista, malgrado le intenzioni di chi ne fece la sigla delle trasmissioni degli occupanti; parla di un improbabile e straziante arrivederci dopo la guerra tra due amanti, una donna e un soldato.

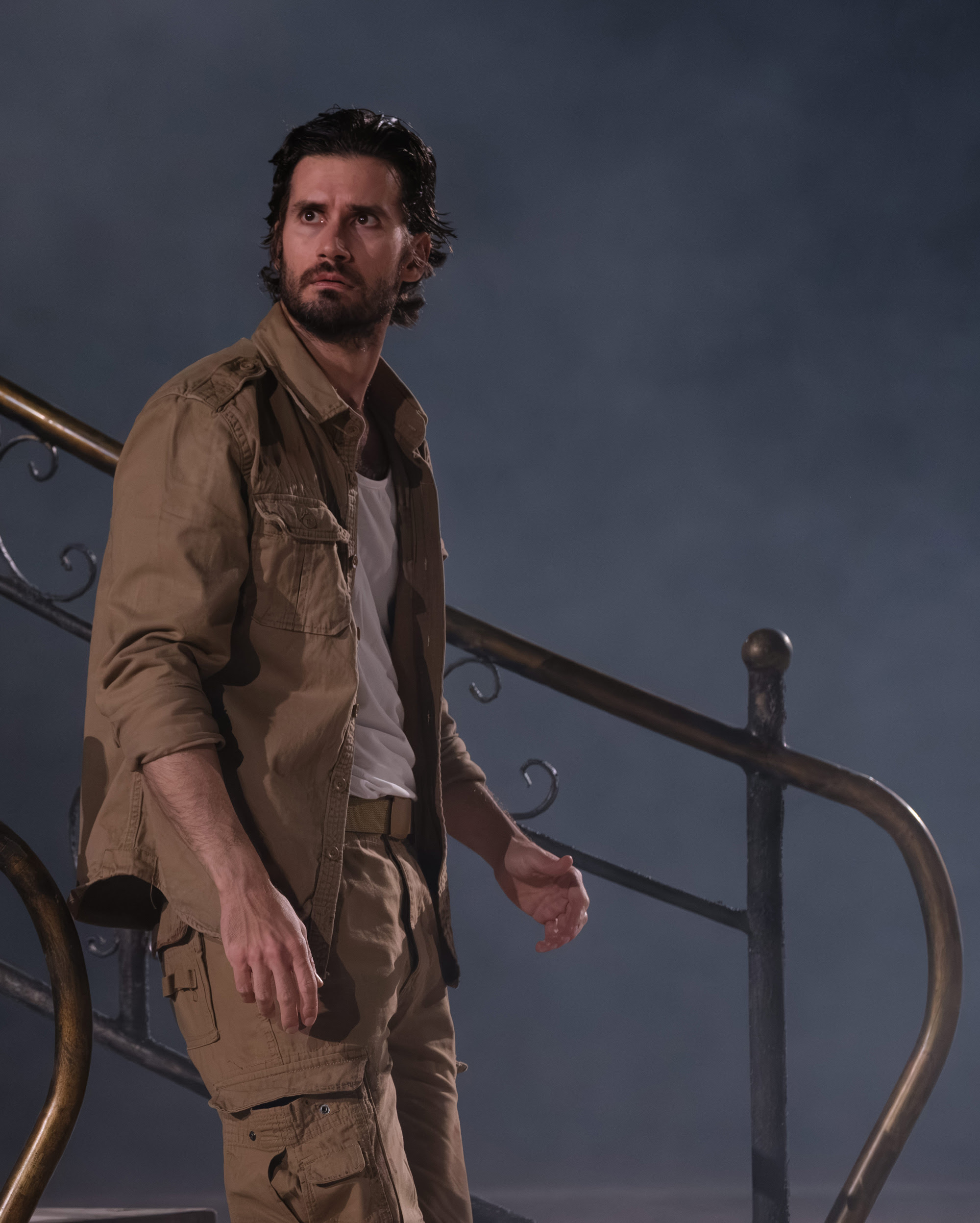

Sotto un lampione, nella sera sconfinata della prima di Electra diretta da Dimitri Tarow per l’Epidaurus Theater Festival 2025, arrivano due soldati, in cerca di quel che hanno lasciato: casa, famiglia, amore. Ma i reduci non riconoscono più la casa, i luoghi, le cose, le persone; tutto è diventato altro, estraneo, ostile.

L’ambientazione e i costumi, come rivela il programma di sala, si ispirano alla pittura di Yannis Tsarouki, ai suoi marinai giovani e pensosi, ai loro corpi desiderabili e malinconici, alla loro pose ricche di solitudine e rimpianti. Quando, alla fine della tragedia, entra in scena Egisto vestito come un dandy in giacca e pantaloni azzurro elettrico con righe bianche si tratta di una vera e propria citazione dall’ironico quadro di Tsarouki, ‘Il pensatore’, del 1936 (vedi sotto).

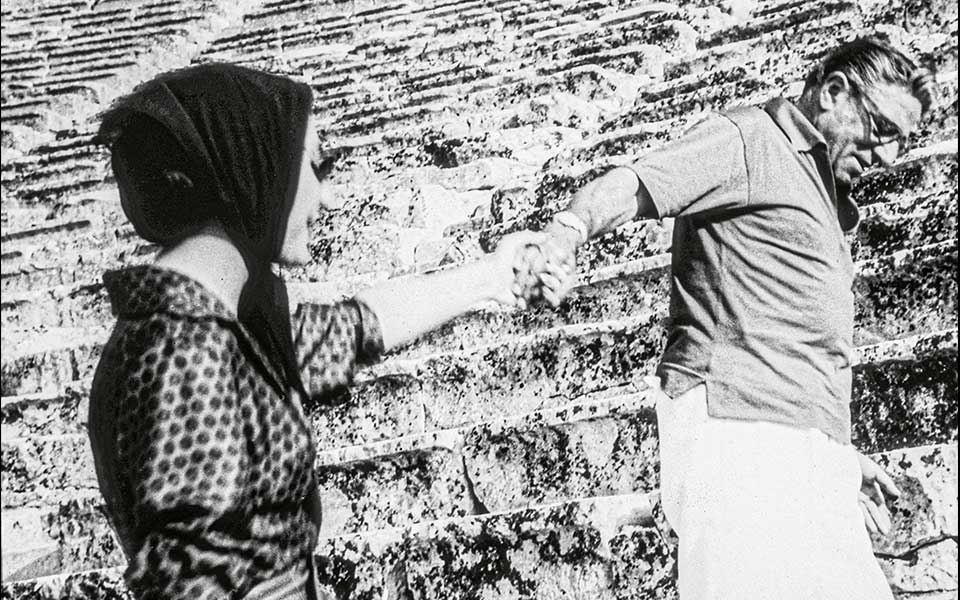

Lo stesso Tsarouki nel 1960 e nel 1961 fu il costumista e lo scenografo della Medea di Cherubini e della Norma interpretate da Maria Callas ad Epidauro. La soprano arrivò sullo yacht del suo per lei fatale amore, Aristotele Onassis, che attraccò nel piccolo porto di Epidauro ‘archaia’. Erano gli anni ruggenti, ed è proprio a quelli che allude la scenografia di questa Electra.

Le donne del coro e Clitemnestra indossano infatti costumi ispirati agli anni del dopoguerra, abiti da ballo swing color pastello o fiorati, segno della speranza di rinascita in un’epoca di grandi sogni e di oblio del passato. In particolare, Crisotemi impersona una spensieratezza necessaria, se si vogliono superare i traumi che altrimenti spezzano e distruggono. Clitemnestra, capelli biondi, rossetto squillante, abito verde zaffiro fa l’eco al modello di Marylin Monroe, evanescente come una nuvola, sventurata come un’eroina tragica. Siamo in un dopoguerra dove tutti vogliono andare avanti e guardare al futuro, ballare, divertirsi, ridere. Anni assai brevi, strozzati in Grecia dalla dittatura, in Europa dal terrorismo e nel mondo dalla guerra fredda.

Alludendo specificamente al secondo dopoguerra, questa Electra ci mette sotto gli occhi le conseguenze della guerra in generale, da quella archetipica di Troia alle contemporanee. La vicenda di Oreste che torna per vendicare il padre, infatti, non è solo una storia familiare di tradimenti e di violenze insopportabili, di traumi e di eredità inevitabili. È la storia di una generazione segnata da un conflitto mondiale che non ha combattuto né voluto, imbrigliata in una catena di odio e di vendetta senza poter scegliere un’altra via. Oreste deve vendicare il padre Agamennone, che è stato ucciso dalla madre Clitemnestra per vendetta; deve vendicare l’onore della famiglia e riprendersi il regno; deve eliminare l’usurpatore Egisto, amante della madre.

Oreste deve infine tener testa a un imperativo etico, assecondare i desideri di sua sorella Elettra, ridotta ad una larva umana, tenuta ai margini perché pericolosa e disturbante, legata da un ricordo malato al padre ucciso, segnata dal trauma e incapace di uscire dal labirinto della disperazione. Elettra qui è una vittima della guerra che non sa e non può guarire dalle sue ferite psichiche. Oreste è il triste esecutore di una vendetta che non ha scelto, il burattino di un meccanismo che non controlla. Nell’orgia di violenza, collettiva e individuale, nessuno si salva e soprattutto nessuno si salva da solo.

Elettra viene messa in scena senza cambiare nulla del testo di Sofocle, in una traduzione chiara e recitata senza enfasi alcuna. Le parti corali sono accompagnate da una musica dal vivo cantilenante, che intende riprodurre ritmi corali tradizionali. I movimenti cadenzati delle donne, anch’essi inscrivibili nella tradizione di danze mediterranee, trovano il culmine performativo nell’esibizione acrobatica di Pilade in mezzo a loro.

Follia, paura, delirio non sono, in questa Electra, componenti del carattere del solo personaggio che dà il nome alla tragedia. Anzi: nonostante il peso della ricezione successiva che l’ha voluta così, l’Elettra di Tarow non è un’esagitata fuori di sé con tensioni criminali o una sessualità torbida. Elettra è una giovane donna che soffre, che incoscientemente pensa che la vendetta allieverà un dolore incoercibile di cui non conosce le cause, uno strazio che la risucchia in un vortice abissale. Non proviamo paura o sconcerto per questa Elettra, ma un’immensa pietà. Elettra è l’anello che non tiene in una catena di crudeltà e odio.

La musica, insieme ai colori pastello e vintage dei costumi e della scenografia, ci immerge in un’atmosfera di rimpianto per quel che fu e che non sarà certamente più. Il nocciolo emotivo di questa messa in scena diventa allora la vita felice di un’infanzia che la guerra ha spezzato bruscamente, di cui restano ricordi vaghi, ombre, il ritornello di una canzonetta che i bambini intonavano insieme.

Davvero quei bambini furono così gioiosi e sereni? Davvero l’amore fra loro fu purissimo e indissolubile? E come si comportava con loro quel padre che non esitò, per ragioni politiche, a dare in sacrificio una delle sue figlie? Che padre era e che marito – quell’uomo che tornò dalla guerra portando come concubina una principessa straniera? E la madre? Chi è Clitemnestra? Una donna umiliata, che ha il coraggio di ribellarsi ad un patriarcato cinico ed oppressivo e di costruirsi un’altra vita, senza esitare ad uccidere? Una donna a cui è stata imposta l’infelicità? Un giocattolo impazzito nelle mani dei maschi che muovono le pedine della guerra? Oppure una ‘madre non-madre’, come la considera Elettra?

La prima dello spettacolo è turbata da un grido di aiuto, qualcuno che chiede un medico e interrompe l’attore che impersona il Precettore, in un teatro vertiginosamente pieno sino alle gradinate più alte, oltre 14mila spettatori che restano col fiato sospeso. Quel grido di aiuto ci riporta all’ estrema vulnerabilità della vita.

Ma il brivido che ci coglie non riguarda solo l’accaduto, che si risolve fortunatamente dopo pochi minuti. Le domande sollevate stasera, infatti, non ci interrogano soltanto sul senso da dare a una vicenda mitologica, per quanto siamo in presenza di una messa in scena filologicamente rispettosa del testo. Le domande riguardano noi e il nostro presente: il riconoscimento reciproco di Elettra e di Oreste ci commuove perché pensiamo a quanti bambini, in queste ore, mentre noi siamo in un paradiso di bellezza, stanno perdendo sotto i bombardamenti gli abbracci di fratelli, sorelle, genitori, che non stringeranno mai più. Il monologo di Elettra ci coinvolge perché ci mette sotto gli occhi un essere umano annientato, disorientato dalla sventura e dall’emarginazione, incapace di distinguere il bene dal male. Persino Clitemnestra non ci appare un mostro e una criminale, ma piuttosto una donna che si è dovuta tenere a galla, che a suo modo è sopravvissuta alla guerra, con egoismo, superficialità, spinta da un’ ansia di vendetta.

Da questa sera di brezze e di sussurri dalle vicine rovine del tempio di Asclepio un pensiero soprattutto resta: la vendetta genera solo vendetta, in una spirale infinita.

Il lampione a olio diventa sempre più fioco, lo stoppino arde a fatica, scende la notte su questa ennesima storia umana di sangue, lutto e follia.

Come dopo ogni guerra, il soldato e la sua amata non torneranno più ad incontrarsi sotto quella luce fioca e romantica.

Restano frammenti, rovine, intermittenze.

Dalle stanze silenziose, dal profondo della terra

Si alza, come in sogno, la tua bocca amata,

quando si diraderà la nebbia

chi sarà con te vicino alla lanterna, Lili Marleen?

Electra beneath the Lamplight of Lili Marleen: Poreia Theatre in Sophocles’ Tragedy at the Athens Epidaurus Festival 2025

At the center of the orchestra of the great theatre of Epidaurus rises the entrance to a bourgeois house from the 1930s: a wrought-iron spiral staircase, green-painted shutters flung wide open—a fragment of a building, an architectural ruin. The rest of the house is gone: the façade, the walls, everything is missing. The doorway opens onto the void of the backstage and the unknown. The oversized French window tilts askew, unhinged, like a gaping mouth ready to swallow whoever dares approach.

The scene is dimly lit by an oil lantern. There are no flowers, no garden beds at the entrance of what may once have been a villa with a garden—only an empty bench in a barren, stony courtyard. From the doorway emerges a sinister mist, clouds of dust, smoke from a fire, ashes of the past.

The lamppost rises above the scene, bathing it in an atmosphere both nostalgic and romantic. One is reminded of the "lantern" at the center of the song broadcast by the military radio station of German-occupied Belgrade during World War II, on August 14, 1941: Lili Marleen, made famous by Marlene Dietrich's dark voice. That song—as is well known—became an anthem of pacifist hope, despite the intentions of those who made it the signature tune of the occupying forces' broadcasts. It tells of an improbable and heartrending farewell between two lovers, a woman and a soldier, hoping to meet again after the war.

Beneath a lamppost, in the boundless twilight of the premiere of Electra, directed by Dimitri Tarow for the Epidaurus Theater Festival 2025, two soldiers arrive in search of what they left behind: home, family, love. But the returning veterans no longer recognize the house, the places, the things, the people; everything has become something else, foreign, hostile.

The setting and costumes, as revealed in the program notes, are inspired by the paintings of Yannis Tsarouchis: his pensive young sailors, their desirable and melancholy bodies, their poses full of solitude and longing. When, at the end of the tragedy, Aegisthus appears dressed like a dandy in an electric-blue jacket and trousers with white stripes, it is a direct quotation from Tsarouchis's ironic 1936 painting The Thinker. Tsarouchis himself was the costume and set designer for Cherubini's Médée and Bellini's Norma, performed by Maria Callas at Epidaurus in 1960 and 1961. The soprano arrived on the yacht of her fatal love, Aristotle Onassis, which docked at the small port of Archaia Epidauros. Those were the roaring years, and it is precisely to that era that the scenography of this Electra alludes.

The chorus women and Clytemnestra wear costumes inspired by the postwar years: swing dance dresses in pastel or floral patterns, symbols of the hope for rebirth in an era of great dreams and willed forgetfulness of the past. Chrysothemis, in particular, embodies a necessary lightness—one must embrace it if the traumas of the past are not to shatter and destroy. Clytemnestra, with her blonde hair, bright red lipstick, and sapphire-green dress, echoes the figure of Marilyn Monroe: evanescent like a cloud, doomed like a tragic heroine. This is a postwar world in which everyone wants to move forward and look to the future, to dance, to have fun, to laugh. Years that were all too brief, cut short in Greece by dictatorship, in Europe by terrorism, and worldwide by the Cold War.

Alluding specifically to the postwar period, this Electra places before our eyes the consequences of war in general—from the archetypal war of Troy to the conflicts of the present day. The story of Orestes returning to avenge his father is not merely a familial tale of betrayal and unbearable violence, of trauma and inescapable inheritance. It is the story of a generation marked by a world war they neither fought nor chose, trapped in a chain of hatred and revenge with no possibility of an alternative path. Orestes must avenge his father Agamemnon, murdered by his mother Clytemnestra in an act of revenge; he must restore the family’s honor and reclaim the kingdom; he must eliminate the usurper Aegisthus, his mother’s lover.

Orestes must also answer to a moral imperative: he must fulfill the wishes of his sister Electra, reduced to a human wraith, marginalized because she is dangerous and disruptive, emotionally bound to the murdered father by a sickly memory, marked by trauma and incapable of escaping the labyrinth of despair. In this version, Electra is a victim of war who cannot and does not know how to heal her psychological wounds. Orestes becomes the sorrowful executor of a revenge he did not choose, a puppet in a mechanism beyond his control. In the orgy of violence—both collective and personal—no one is saved, and above all, no one is saved alone.

Electra is staged here without any alteration to Sophocles' original text, presented in a clear translation and delivered without theatrical emphasis. The choral parts are accompanied by live, chant-like music, evoking traditional choral rhythms. The measured movements of the women, themselves evocative of Mediterranean dance traditions, culminate in the acrobatic performance of Pylades among them.

Madness, fear, and delirium are not limited to the character who gives her name to the tragedy. In fact, contrary to the dominant reception that has often framed her this way, Tarow's Electra is not a frenzied, unhinged figure driven by criminal impulses or dark sexuality. She is a young woman in pain, who unconsciously believes that vengeance will alleviate an uncontainable sorrow whose causes she does not understand—a grief that draws her into a bottomless vortex. We do not fear this Electra, nor are we unsettled by her; rather, we feel overwhelming pity. Electra is the broken link in a chain of cruelty and hatred.

The music, together with the pastel and vintage tones of the costumes and scenography, immerses us in an atmosphere of longing for what once was and will never be again. The emotional core of this production thus becomes the memory of a happy childhood brutally cut short by war—a childhood of which only vague memories remain: shadows, the refrain of a children's song once sung in chorus.

Were those children truly so joyful and serene? Was the love between them truly pure and indissoluble? And what kind of father was the man who, for political reasons, did not hesitate to sacrifice one of his daughters? What kind of father, and what kind of husband, was the man who returned from war with a foreign princess as his concubine? And the mother? Who is Clytemnestra? A humiliated woman with the courage to rebel against a cynical and oppressive patriarchy and to build a new life without hesitation—even if it means killing? A woman to whom unhappiness was imposed? A frenzied toy in the hands of men who move the pawns of war? Or a "non-mother," as Electra considers her?

The premiere of the performance is interrupted by a cry for help, someone calling for a doctor, cutting off the actor playing the Tutor in a theatre vertiginously full to its highest tiers—more than 14,000 spectators holding their breath. That cry brings us back to the ultimate fragility of life.

But the chill that overtakes us is not only due to what has just occurred—which, fortunately, is resolved within minutes. The questions raised this evening concern not only the meaning of a mythological tale, however philologically faithful the production may be to the text. These questions concern us and our present: the mutual recognition between Electra and Orestes moves us because we think of how many children, at this very moment, while we sit in a paradise of beauty, are losing to bombardments the embrace of brothers, sisters, parents—whom they will never hold again. Electra’s monologue strikes us because it reveals a human being annihilated, disoriented by misfortune and marginalization, unable to distinguish right from wrong. Even Clytemnestra does not appear to us as a monster or a criminal, but rather as a woman who has struggled to stay afloat, who in her own way has survived the war—with selfishness, superficiality, driven by a desire for revenge.

But the chill that overtakes us is not only due to what has just occurred—which, fortunately, is resolved within minutes. The questions raised this evening concern not only the meaning of a mythological tale, however philologically faithful the production may be to the text. These questions concern us and our present: the mutual recognition between Electra and Orestes moves us because we think of how many children, at this very moment, while we sit in a paradise of beauty, are losing to bombardments the embrace of brothers, sisters, parents—whom they will never hold again. Electra’s monologue strikes us because it reveals a human being annihilated, disoriented by misfortune and marginalization, unable to distinguish right from wrong. Even Clytemnestra does not appear to us as a monster or a criminal, but rather as a woman who has struggled to stay afloat, who in her own way has survived the war—with selfishness, superficiality, driven by a desire for revenge.

From this evening of breezes and whispers rising from the nearby ruins of the temple of Asclepius, one thought remains above all: revenge breeds only more revenge, in an endless spiral.

The oil lamp grows ever dimmer; the wick burns weakly as night falls upon yet another human tale of blood, mourning, and madness.

As after every war, the soldier and his beloved shall never again meet beneath that faint, romantic light.

All that remains are fragments, ruins, flickers in the dark.

From the silent rooms, from the depths of the earth,

Rises, as in a dream, your beloved mouth;

When the mists finally lift,

Who will stand by the lantern with you, Lili Marleen?

Translation Giorgos Chimonas

Direction Dimitri Tarlow

Set & Costume design Paris Mexis

Music composition Fotis Siotas

Lighting design Alekos Anastasiou

Choreography Markella Manoliadi

Dramaturgy collaborator Eri Kyrgia

Sound design Ilias Flammos

Assistant to the director Dimitra Koutsokosta, Aristi Tselou

Assistant to the set & costume designer Despoina-Maria Zachariou

Assistant choreographer Maro Stavrinou

Assistants to the lighting designer Charis Dallas, Nafsika Christodoulakou

Cast Giannis Anastasakis Pedagogue, Grigoria Metheniti Chrysothemis, Loukia Michalopoulou Electra, Nikolas Papagiannis Aegisthus, Ioanna Pappa Clytemnestra, Anastasis Roilos Orestes, Periklis Siountas Pylades

Chorus Margarita Alexiadi, Asimina Anastasopoulou, Ioanna Demertzidou, Ioanna Lekka, Eleni Kilinkaridou-Sisti, Lydia Stefou, Anna Symeonidou, Chara Tzoka, Eleni Vlachou

On-stage musicians Fotis Siotas, Tasos Misirlis

Language Greek (with Greek and English surtitles)

Photo @ Patroklos Skaphidas