English version below

In principio era la ripetizione. L’uomo impara a camminare ripetendo dei gesti, a parlare ripetendo dei suoni, conta il tempo attraverso la ripetizione del succedersi di luce e buio, si orienta nello spazio ricordando vie già percorse e costruendo mappe dei suoi spostamenti.

La ripetizione non è dunque monotonia e non va considerata errore estetico – come potrebbe sembrare ad epoche che hanno il culto di un’inesistente originalità.

Secondo Freud, la coazione a ripetere riguarda l’esperienza traumatica. Si rivive il trauma proprio per liberarsi di esso. La ripetizione si configura come una sorta di tecnica del sé, più o meno efficace, per sopravvivere al proprio passato traumatico. La ripetizione contiene dunque un elemento catartico. Per Michel Foucault, la ripetizione è allora l’immensa possibilità di rottura che risiede in ogni minima differenza realizzata attraverso i minuscoli gesti dell’arte, del linguaggio, della vita quotidiana. Anche per Foucault, sebbene in senso diverso da Freud, la ripetizione contiene un elemento catartico. Infatti – afferma Foucault – persino la ripetizione apparentemente più insensata rivela che c’è sempre uno strappo, «un tremolìo di luce», un dettaglio che rompe la ripetizione, la rende diversa, apre uno spiraglio per qualcosa di nuovo che faccia uscire dal loop della monotonia.

La ripetizione di immagini e discorsi che rappresentano l’orrore genera (o dovrebbe generare) la potenzialità del cambiamento, il punto di rottura, la differenza. Giorgio Agamben, in un articolo in cui parla della ripetizione a proposito del cinema di Guy Debord, afferma: «Quando Debord mostra un estratto di un telegiornale, la forza della ripetizione consiste nel far sì che esso cessi di essere un fatto compiuto per diventare, per così dire, di nuovo possibile. Ci si chiede: «Com’è stato possibile?» – è la prima reazione – ma allo stesso tempo si comprende che sì, tutto è possibile. Hannah Arendt definì un giorno l’esperienza estrema dei campi di sterminio con il principio del «tutto è possibile», persino l’orrore che ci viene ora mostrato. È in questo senso estremo che la ripetizione restituisce possibilità».

La ripetizione ha perciò a che fare con la tragedia greca e con ogni tragedia in generale. Perché ripetere la vicenda di Edipo, perché quella di Antigone, o ancora di Medea, di Alcesti, perché ripeterla davanti a un pubblico che già ne conosce le vicende? Non si tratta solo di una ripetizione che ha valenza estetica, ossia che spinge il pubblico a verificare in che modo lo stesso racconto mitologico venga ripetuto e performato.

La ripetizione svincola il fatto mitologico da ogni legame spazio-temporale, concede a esso un’universalità aberrante che consiste non solo nella possibilità, ma nell’inevitabilità che lo schema della vicenda tragica, nella sua essenzialità, si ripeta.

La vicenda del parricida e incestuoso Edipo è tragica nella possibilità che la stessa vicenda si ripeta, che il meccanismo venga re-innescato e ri-performato, che la macchina infernale, come la definiva Jean Cocteau, si rimetta in moto.

Nello stesso tempo la tragedia, nella sua ripetitività e riproducibilità, contiene la propria intrinseca moralità. La consapevolezza che l’evento tragico possa ripetersi offre comunque uno spiraglio di speranza, la speranza che la ripetizione possa essere interrotta, possa generare una differenza, minima o sostanziale, uno scardinamento negli ingranaggi della metaforica macchina che ripete e riproduce cose e fatti.

La rievocazione di un fatto doloroso e tragico non suscita il desiderio della sua ripetizione; ma mentre offre un godimento estetico nello spettacolo tragico (un paradosso segnalato già da Friedrich Schiller), concedendo la salvezza della distanza, temporale e spaziale, offre anche la possibilità di avere un diverso atteggiamento di fronte alla ripetizione.

Ripetere le immagini dell’Olocausto ha senso non perché queste offrono uno spettacolo sull’orrore e dell’orrore ma proprio perché attestano la possibilità che i fatti che raccontano si ripetano. Non a caso in questi tremendi giorni si è detto che le immagini da Gaza, sia dei superstiti ostaggi israeliani sia dei gazawi, ripetono quelle di Auschwitz. Le rovine di Gaza ripetono quelle della bomba atomica di Hiroshima e Nagasaki.

Il rischio di assuefarsi alla ripetizione è altissimo, si può chiamare rassegnazione. Se tutto si ripete, ogni azione, anche la più terribile, diventa atto irriflesso e inevitabile, come camminare, parlare, pettinarsi, portarsi il cibo alla bocca.

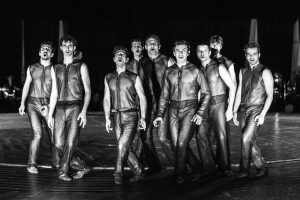

Il regista tedesco Ulrich Rasche ha reso la ripetizione il principio interpretativo della tragedia greca: nelle sue re-visioni delle tragedie greche, i personaggi si muovono su una scena che è un tappeto rotante, con gesti studiatissimi, di lentezza e connessione esasperante, in una danza che non procede nello spazio, in un movimento che si basa su una tensione dei corpi nelle loro membra e nei corpi tra loro.

Proprio la ripetizione di ciò che si assomiglia moltissimo ma non è mai lo stesso – sembra dirci Rasche – è il nocciolo del ‘tragico’, non solo e tanto nella sua dimensione estetica, ma soprattutto in quella storica ed esistenziale.

L’essere umano stabilisce connessioni fisiche ed emotive con gli altri uomini, con gli oggetti, con la natura, con l’ambiente, consumando la propria esistenza nella ripetizione di situazioni che appartengono alla sua memoria ancestrale, senza riuscire a interrompere quel fluire apparentemente identico che lo trascina verso l’abisso, senza concedergli alcuna autonomia. Tragica diventa allora per l’essere umano la difficoltà di manifestare la propria differenza, in una lotta contro il ritorno dell’identico che travolge l’individuo e lo rende parte di un meccanismo che lo ingloba totalmente, rendendolo alla pari di una cosa, di un ingranaggio che ruota insieme ad altri ingranaggi senza alcuna coscienza del cambiamento o del progresso e senza possibilità di uscire fuori da metaforici binari.

Quest’estate, nell’atmosfera emotiva del teatro greco di Epidauro e di un mondo in guerra, Ulrich Rasche ha messo in scena una discussa Antigone.

Si tratta di un’Antigone buia, corale, luttuosa, in cui i personaggi sono impegnati in una danza macabra per la sopravvivenza: il coro per la sopravvivenza della città, Creonte per la sopravvivenza del potere, Antigone per la sopravvivenza della pietà e della compassione.

Nell’Antigone di Rasche, ogni gesto dei personaggi implica uno sforzo tremendo, esige una tensione spasmodica di ogni parte del corpo, in movimenti corali che alternano coesione e disgregazione, come se le singole figure danzassero seguendo il pulsare di un cuore universale, il respiro dell’universo.

La tensione raggiunge l’apice nel confronto tra Creonte e Antigone, che partono da un abbraccio iniziale e poi si separano, tendendosi l’una verso e contro l’altra senza mai più toccarsi e senza mai più stringersi; due figure unite da un’invisibile corrente che le trascina insieme e che insieme costituiscono un microcosmo fisico ed emotivo; due figure tenute insieme da un flusso emotivo di sentimenti negativi, rabbia, odio, disprezzo. Il loro è uno scontro inconciliabile, un conflitto tanto più potente proprio perché non giunge al sangue, alla ferita, alla collisione.

Eppure questa guerra condotta solo con parole taglienti e mortali come coltelli, porta ad una generale conflagrazione, alla rovina che eccede la discussione tra i due contendenti per abbattersi come una cascata sul mondo intero.

Tutto finisce per crollare nell’abisso. L’immane ed evanescente conflitto tra due personaggi, uno incomparabilmente più forte dell’altro, resta senza vincitori e vinti.

L’Antigone di Rasche diventa così – persino malgrado le intenzioni del regista – una proiezione ipnotica del presente, che ‘filma’ la parvenza di equilibrio in cui il mondo sta procedendo su una linea sottilissima di confine: da una parte ci sono i potenti, prepotenti e sanguinari, che infieriscono sui cadaveri e rinchiudono nelle grotte senza luce, privandoli del cibo, innocenti inermi, con l’intento di aspettare la loro morte; dall’altra c’è chi difende il principio unico della identità e dignità umana anche nella morte, chi rispetta il legame di sangue, anche se quel sangue appare incestuoso e corrotto, chi non combatte con le armi e gli eserciti ma con le nude mani e con pugni di polvere e di pietre.

Nelle note di regia, Ulrich Rasche afferma di aver voluto dare enfasi al ruolo di Creonte, avvalorando un’interpretazione dell’Antigone diffusa di recente anche in Italia (per esempio da Eva Cantarella e Luciano Violante) per cui Creonte sarebbe giustificato dalla ragione di Stato e Antigone sarebbe un’aristocratica conservatrice che agisce per ‘egoismo sociale’, un’interpretazione che non condivido e peraltro assai vecchia (vedi almeno il capitolo su Alfred Döblin nel mio L’ora di Antigone dal nazismo agli anni di piombo, 2012). Ma nonostante le affermazioni del regista, la sua Antigone va in altro senso.

Creonte è un tiranno, incapace di giustizia e animato da spirito di vendetta, che nella sua cecità e nelle sue manie di persecuzione comincia la sua personale guerra per rafforzare il suo potere individuale, e comincia con lo sterminio degli oppositori più deboli, infierendo su coloro che più facilmente possono essere schiacciati, i gruppi marginali, come i soldati e le donne. Creonte è un tiranno che usa l’esposizione del cadavere del nemico come monito e come deterrente per l’opposizione interna, ossessionato dal denaro e dal suo valore, sicuro di essere circondato da corrotti perché lui stesso corruttibile. Il potere di Creonte tra l’altro non difende affatto lo Stato e la comunità, come il tiranno vorrebbe mostrare nel suo primo propagandistico discorso, ma lo precipita di nuovo nel caos e nella morte, proprio quando c’era più bisogno di pace. Polinice, il fratello di Antigone, ha attaccato la città da nemico, un attacco sanguinoso, cruento, che è stato però respinto. Creonte non sa costruire la pace, non vuole costruirla e annulla anche i risultati della vittoria.

Antigone è la resistente ad un potere che si compiace di sé stesso; anche Antigone conosce la violenza ma non può praticarla, e perciò raschia con le unghie la polvere da terra per coprire i cadaveri ed infine diventa lei stessa statua di pietra, come Niobe. Antigone attesta, con la sua fame imposta e la sua disperazione, l’impossibilità di sfuggire alla forza delle armi, ed anche di sfuggire alla terra, al sangue, alla pesante eredità familiare, di cui è comunque vittima, sebbene vittima orgogliosa.

I nomi di Creonte e Antigone sono fuori dal tempo storico, ma nel tempo seriale della tragedia e nel suo presente assoluto: la loro tensione e la loro vicenda si ripetono, sempre e sempre, sotto i nostri occhi, e noi ne siamo diversamente coinvolti.

Siamo coinvolti come spettatori muti e catturati nella danza circolare dei personaggi, presi nel loro vortice psicologico e resi incapace di agire, mentre Antigone viene sommariamente processata e affamata, mentre viene sepolta viva, mentre il corpo del fratello viene lasciato come pasto dei cani e degli avvoltoi. Siamo il coro che striscia in scena fuori dai tunnel, che reclama la pace, zombie sfiniti che cercano il sole e la liberazione, che rivolgono lo sguardo in alto e sono colti da una pioggia di bombe. Oppure siamo lì tra nubi di polvere che si alzano dalle macerie, divenuti noi stessi statue di arida roccia, bersagli umani considerati non più umani, considerati niente. O siamo i medici che salvano e curano e muoiono persino di fame o sotto i bombardamenti; i giornalisti che cercano qualcosa che sanno chiamare ‘verità’. Siamo nella chiesa della Sacra Famiglia, protetti solo dalla nostra fede, luogo di martirio per errore. Siamo i soldati che obbediscono agli ordini, come agli ordini obbedirono, con zelo e anche con divertimento, i soldati tedeschi e le SS. Siamo le vittime e i carnefici. Siamo i potenti e gli impotenti. Siamo chi ha tutto e chi non ha nulla. Siamo Creonte e Antigone. E tutto si ripete.

Tutto si ripete, come nel loop senza scampo di Il figlio di Saul di László Nemes (2015), per portare solo un esempio di questa estetica tragica della ripetizione, estetica oscura, monotona come monotono è il ripetersi dell’orrore, anche quello dell’indifferenza, come in La zona di interesse (2023) di Jonathan Glazer.

E nel ripetersi, tutto diventa possibile e ri-proponibile. Starebbe a noi trovare lo strappo nella rete, il principio o la fede che ci aiuti a inventare quel qualcosa di nuovo, a creare la differenza, che trasformi la ripetizione da ricordo e reminiscenza in progetto per il futuro.

«Ripetizione e ricordo sono lo stesso movimento, tranne che in senso opposto: l’oggetto del ricordo infatti è stato, viene ripetuto all’indietro, laddove la ripetizione propriamente detta ricorda il suo oggetto in avanti», ha scritto Søren Kirkegaard, che però credeva cristianamente all’eternità.

Nell’Antigone di Sofocle lo strappo nella rete, il «tremolio di luce» non c’è e non resta che il nulla.

Repetition and Tragedy: From Antigone to Gaza

In the beginning, there was repetition.

Human beings learn to walk by repeating movements, to speak by repeating sounds, they count time through the repetition of the succession of light and darkness, and they orient themselves in space by remembering already-trodden paths and constructing maps of their movements.

Repetition, therefore, is not monotony and should not be regarded as an aesthetic error—as it might appear to epochs that worship a non-existent originality.

According to Freud, the compulsion to repeat is linked to traumatic experience. One relives the trauma precisely in order to be freed from it. Repetition thus functions as a kind of technique of the self—more or less effective—for surviving one’s traumatic past. Repetition therefore contains a cathartic element.

For Michel Foucault, repetition is the immense possibility of rupture that resides in every minimal difference brought about through the tiniest gestures of art, language, and everyday life. For Foucault too—albeit in a different sense than Freud—repetition contains a cathartic element. Indeed, Foucault states that even the most seemingly senseless repetition reveals that there is always a tear, “a flicker of light,” a detail that breaks the repetition, makes it different, and opens a crack for something new to emerge—something that might break the loop of monotony.

The repetition of images and discourses that represent horror generates (or should generate) the potential for change, the breaking point, the difference.

Giorgio Agamben, in an article in which he discusses repetition with regard to the cinema of Guy Debord, writes:

“When Debord shows a clip from a newscast, the power of repetition consists in making it cease to be a completed fact, and instead become, so to speak, possible once again. One asks: ‘How was this possible?’—that is the first reaction—but at the same time one understands that yes, everything is possible. Hannah Arendt once defined the extreme experience of the extermination camps with the principle of ‘everything is possible,’ even the horror that is now being shown to us. It is in this extreme sense that repetition restores possibility.”

Repetition is therefore intimately connected to Greek tragedy—and to all tragedy in general.

Why repeat the story of Oedipus? Why that of Antigone, or again of Medea, of Alcestis? Why perform it before an audience that already knows how the story ends?

This is not merely a repetition with aesthetic value, that is, one that pushes the audience to observe how the same mythological narrative is repeated and performed.

Repetition detaches the mythological event from any spatial-temporal bond; it grants it a disturbing universality, consisting not only in the possibility, but in the inevitability of the tragic pattern’s recurrence—in its essential form.

The story of Oedipus, the parricide and the incestuous son, is tragic in the possibility that the same story might repeat itself—that the mechanism may be re-triggered, re-performed, that the infernal machine, as Jean Cocteau called it, may once again be set into motion.

At the same time, tragedy, in its repetitiveness and reproducibility, contains its own intrinsic morality. The awareness that the tragic event may repeat itself offers, nonetheless, a glimmer of hope: the hope that the repetition may be interrupted, that it may generate a difference—be it minimal or substantial—a disruption in the gears of the metaphorical machine that repeats and reproduces events and deeds.

The recollection of a painful and tragic event does not provoke a desire for its repetition; yet, while it offers aesthetic pleasure in the tragic spectacle (a paradox already noted by Friedrich Schiller), granting the safety of temporal and spatial distance, it also allows for the possibility of adopting a different stance toward repetition.

To repeat the images of the Holocaust makes sense not because they offer a spectacle of horror or about horror, but precisely because they testify to the possibility that the events they depict may recur.

Not by chance, in these dreadful days, it has been said that the images coming from Gaza—whether of the surviving Israeli hostages or of the Gazan civilians—echo those of Auschwitz. The ruins of Gaza echo those of the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

The risk of becoming desensitized to repetition is immense—it might be called resignation. If everything repeats itself, then every action, even the most terrible, becomes a reflexive and inevitable act—like walking, speaking, brushing one’s hair, or bringing food to one’s mouth.

The German director Ulrich Rasche has made repetition the interpretive principle of Greek tragedy. In his re-visions of ancient tragedies, the characters move on a stage that is a rotating platform, performing highly choreographed gestures of exasperating slowness and interconnectedness, in a dance that does not advance through space—a movement based on the tension of bodies in their limbs and of bodies in relation to one another.

It is precisely the repetition of what appears almost identical yet is never the same—Rasche seems to tell us—that constitutes the core of the tragic, not merely in its aesthetic dimension, but above all in its historical and existential one.

The human being forms physical and emotional connections with other human beings, with objects, with nature, with the environment, exhausting their existence in the repetition of situations rooted in ancestral memory, without managing to interrupt that seemingly identical flow that drags them toward the abyss, granting no autonomy.

Tragic, then, becomes the human being’s difficulty in expressing their own difference—in a struggle against the return of the same, which overwhelms the individual and renders them part of a mechanism that fully absorbs them, reducing them to the level of a thing, a cog turning with other cogs, without any awareness of change or progress, and without the possibility of stepping off those metaphorical tracks.

This summer, in the emotionally charged setting of the ancient theatre of Epidaurus and against the backdrop of a world at war, Ulrich Rasche staged a controversial Antigone.

It is a dark, choral, mournful Antigone, in which the characters are caught in a danse macabre for survival: the chorus for the survival of the city, Creon for the survival of power, Antigone for the survival of piety and compassion.

In Rasche’s Antigone, every gesture made by the characters entails tremendous effort, demanding spasmodic tension in every part of the body, in collective movements that alternate cohesion and disintegration, as if the individual figures were dancing to the pulse of a universal heart, to the breath of the cosmos.

Tension reaches its peak in the confrontation between Creon and Antigone, which begins with an embrace and then shifts into separation: they stretch toward and against one another without ever touching again, without ever embracing again. They are two figures bound by an invisible current that drags them together, forming a physical and emotional microcosm; two figures held together by an emotional flow of negative feelings—anger, hatred, contempt.

Theirs is an irreconcilable clash, a conflict made all the more powerful by the fact that it does not culminate in blood, in wounds, or in collision.

And yet this war, fought solely with words as sharp and deadly as knives, leads to a general conflagration, to a ruin that exceeds the dispute between the two opponents and crashes down like a waterfall upon the entire world.

Everything ends up collapsing into the abyss. The immense and elusive conflict between two characters—one incomparably stronger than the other—remains without victors or vanquished.

Rasche’s Antigone thus becomes—perhaps even in spite of the director’s intentions—a hypnotic projection of the present, a filmic vision of the fragile balance in which the world moves along an exceedingly thin borderline: on one side stand the powerful—overbearing and bloodthirsty—who abuse corpses and imprison the innocent and defenseless in lightless caves, depriving them of food, waiting for them to die.

On the other side are those who defend the unique principle of human identity and dignity, even in death; those who honor the bond of blood, even when that blood seems incestuous and corrupted; those who do not fight with weapons or armies, but with bare hands, with handfuls of dust and stones.

In his director’s notes, Ulrich Rasche declares that he wanted to emphasize the role of Creon, endorsing an interpretation of Antigone that has recently gained traction in Italy as well (for example in the works of Eva Cantarella and Luciano Violante), according to which Creon is justified by reasons of state and Antigone is a conservative aristocrat acting out of “social egoism”—an interpretation I do not share and which is, in any case, quite dated (see at least the chapter on Alfred Döblin in my L’ora di Antigone. Dal nazismo agli anni di piombo, 2012).

Creon is a tyrant, incapable of justice and driven by a spirit of vengeance. In his blindness and persecution mania, he begins his own personal war to consolidate his individual power, starting with the extermination of the weakest opponents, lashing out at those who can be most easily crushed: the marginal groups, such as soldiers and women.

Creon is a tyrant who uses the public display of the enemy’s corpse as a warning and a deterrent to internal dissent, obsessed with money and its value, convinced he is surrounded by the corrupt because he himself is corruptible.

Creon’s power does not defend the state and the community, as the tyrant seeks to portray in his initial propagandistic speech; rather, it plunges them once more into chaos and death—precisely when peace was most needed. Polynices, Antigone’s brother, attacked the city as an enemy, in a bloody and violent assault, but that assault was repelled. Creon does not know how to build peace; he does not want to build it, and he even undoes the gains of victory.

Antigone is the one who resists a power enamored of itself.

She, too, knows violence but cannot wield it. So she scrapes dust from the ground with her fingernails to cover the corpses and finally becomes herself a statue of stone, like Niobe.

Antigone bears witness, through her forced starvation and despair, to the impossibility of escaping the power of arms—and of escaping the land, the blood, the heavy familial inheritance of which she is nonetheless a victim, though a proud one.

The names of Creon and Antigone lie outside of historical time, but exist in the serial time of tragedy and its absolute present: their tension, their story, repeats itself—again and again—before our eyes, and we are implicated in it in different ways.

We are implicated as mute spectators, caught in the circular dance of the characters, drawn into their psychological vortex and rendered unable to act, while Antigone is summarily judged and starved, while she is buried alive, while the body of her brother is left as food for dogs and vultures.

We are the chorus crawling onto the stage from tunnels, crying out for peace—exhausted zombies seeking the sun and deliverance—lifting our gaze upward, only to be struck by a rain of bombs.

Or we are there, among the clouds of dust rising from the rubble, turned into statues of arid rock ourselves—human targets no longer considered human, considered nothing.

Or we are the doctors who heal and save, and die of hunger or under bombardment; the journalists searching for something they still know how to call “truth.”

We are inside the Church of the Holy Family, protected only by our faith—a place of martyrdom by mistake.

We are the soldiers who follow orders, just as the German soldiers and the SS once did—with zeal and even with enjoyment.

We are the victims and the executioners. We are the powerful and the powerless.

We are those who have everything and those who have nothing.

We are Creon and Antigone.

And everything repeats.

Everything repeats, as in the inescapable loop of Son of Saul (Saul fia, 2015) by László Nemes—just one example of this tragic aesthetic of repetition: a dark aesthetic, monotonous as the repetition of horror itself is monotonous, including the horror of indifference, as in The Zone of Interest (2023) by Jonathan Glazer.

And in this repetition, everything becomes possible again—re-presentable.

It would be up to us to find the tear in the net, the principle or the faith that might help us to invent something new, to create the difference that transforms repetition from memory and recollection into a project for the future.

“Repetition and recollection are the same movement, except in opposite directions: for what is recollected has been, is repeated backward, whereas genuine repetition recalls what is to come, forward,” wrote Søren Kierkegaard—though he believed, in a Christian sense, in eternity.

In Sophocles’ Antigone, the tear in the net—the “flicker of light”—is absent, and nothing remains but the void.

Riferimenti essenziali /Essential References:

Baldacci, Cristina, et al. Over and Over and Over Again: Reenactment Strategies in Contemporary Arts and Theory. Online-Ausgabe (PDF). Berlin: ICI Berlin Press, 2022. https://doi.org/10.37050/ci-21.

Holzhey, Christoph F. E., et al. Re-: An Errant Glossary. Berlin: ICI Berlin Press, 2019

Agamben, G. Il cinema di Guy Debord, in E. Ghezzi – R. Turigliatto, (a cura di), Guy Debord (contro) il cinema, Milano: il Castoro, 2001.

Kierkegaard, S. La ripetizione, a cura di Dario del Borso, Milano: BUR, 2014

Viccei, R. La danza circolare del pensiero, Fata Morgana Web https://www.fatamorganaweb.it/antigone-di-sofocle-regia-di-ulrich-rasche-al-teatro-antico-di-epidauro/